|

|

As a result of the popularity and demand for They Came Before Columbus, Dr. Van Sertima was exhilarated and fueled by your enthusiasm. Its success, beyond doubt, confirmed that we were not satisfied with the mere teachings of our captured, the downtrodden, and enslaved. There was so much more to be said - a range of knowledge across the world that was yet to be taught, to be understood... to be realized and, most importantly, to be proud of. And so, we looked forward to an unveiling of our long-lost, ancient and modern comprehensive history.

This is not to say that Dr. Van Sertima, and all of today's African-centered scholars, have not stood on the shoulders of the forward thinking pillars of strength, that came before them. These prior scholars produced outstanding research with which to educate the public, and provide a platform for further study. They tapped into every source of media available to them. This invaluable knowledge, simply, did not have the capability of the vast distribution methods available to us today. Many educators, though well-intentioned, were locked into an old and incomplete curriculum and, sometimes, an outmoded point of view. Dr. Van Sertima, and many other scholars, whom the Journal comprises, knew we had been, more or less, duly and exhaustively educated about a past that did not give breadth, depth, or credence to our rich and illustrious legacies.

The experience and knowledge of chattel slavery is, of course, as important to our scrutiny and understanding as our current intellectual pursuits. But we needed a balance in order to go beyond the dark side of our history and breathe in a new chapter of fresh air... the air and honesty that would allow us, and our future generations, the motivation to move forward, armed with faith in the future.

With the enabling tools of education, cohesion, truth, and determination, we can live up to who we really are - to stand tall with our strength of overriding struggles, and that of celebrating the majesty of our African heritage. Hence, our accomplishments, and the possibility of a more engaging, worldwide future is inevitable.

Below each book cover, is the synopsis of each book:

|

|

|

| More than twenty-five years have passed since They Came Before Columbus appeared, in which Van Sertima presented most of the facts that were then known about the links between Africa and America before Columbus. But since then, many more sculptures have emerged from the earth or from the back rooms of private collections. New stone heads have surfaced in recent excavations while a very old one with a seven-braided Egyptian hairstyle has come out of a century of obscurity into sudden prominence. Far more sophisticated analyses may now be presented of ancient African astronomy, map-making, scripts, navigation, trade routes, pyramidal structures, linguistic connections, technological and ritual complexes. In this collective work, Van Sertima is joined by half a dozen other colleagues. The work focuses largely on contact between Africa and America towards the close of the Bronze Age (circa 948-680 B.C.) and the Mandingo-Songhay trading voyages (from early fourteenth to late fifteenth centry). (170 illus.) |

|

This volume provides an overview of the black queens, madonnas and goddesses who dominated the history and imagination of ancient times. The authors have concentrated on Ethiopia and Egypt because the documents in the Nile Valley are voluminous compared to the sketchier record in other parts of Africa, but also because the imagination of the world, not just that of Africa, was haunted by these women. They are just as prominent a feature of European mythology, as of African reality. The book is divided into three parts: Ethiopian and Egyptian queens and Goddesses; Black Women in Ancient Art; Conquerers and Courtesans. There are also chapters on the diffusion into Europe of the African goddess, Isis, and on the great scientist, Hypatia, whose African ancestry during the Greek-invader period is deduced not only by her lineage, but by a comparative study of the rights of African and European women. (88 illus.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

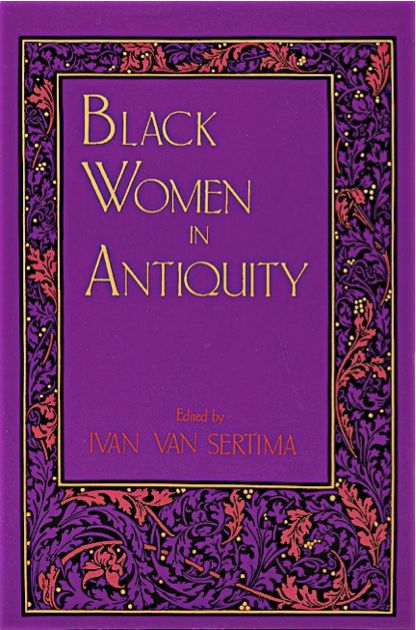

| Co-edited with guest editor, Larry Obadele Williams, this book reviews the life and thought of an African who has left a major impact upon the world. He was the Senegalese physicist, historian and linguist, Dr. Cheikh Anta Diop, who was born in Diourbel, Senegal on Dec. 29, 1923, and died in Dakar on Feb. 7, 1986. No figure in the field of African civilization studies has been more highly regarded in the French and English-speaking world than Diop. In 1966 the First World Festival of Arts and Culture attributed jointly to the late W.E.B. Du Bois and Dr. Cheikh Anta Diop its "Award of the Scholar who has exerted the greatest influence on Negro thought in the 20th century." The book has the finest essays by, extended interviews with, and detailed analyses of, Diop. (98 illus.) |

|

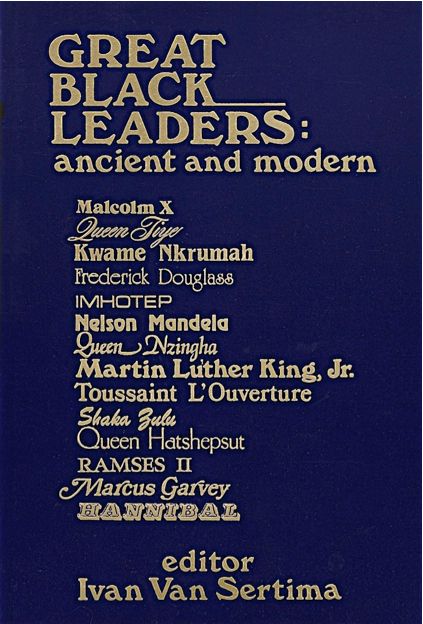

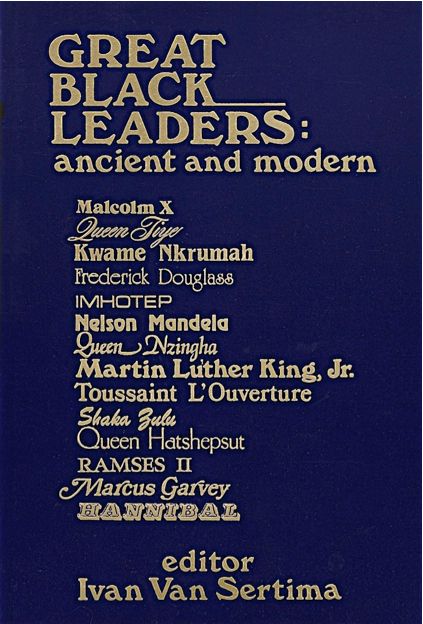

Any selection of leaders, whatever the criteria, is inherently subjective, and this collection does not pretend to be comprehensive. It does establish clear criteria for inclusion, focusing on outstanding individuals from America, Africa, and the Caribbean, who are clearly of global, and not solely national, significance. Leaders from a number of historical epochs were selected and the editor has also included material on outstanding women leaders (Queens Tiye, Hatshepsut, Nzingha). Leaders who had captured the world's imagination (Shaka) or who had profoundly affected the modern period (Kwame Nkrumah) are also represented. With one exception (Nelson Mandela) the individuals described are no longer living, to ensure that time warrants a consensus about their significance. (120 illus.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

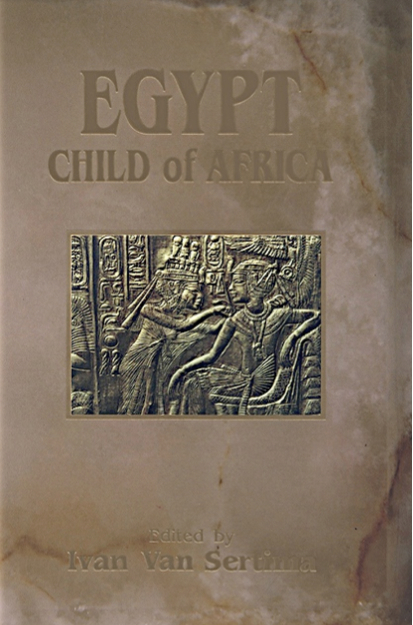

| This issue seeks to answer two questions: First, whether ancient Egyptians were predominantly African or Africoid in a physical sense during the major native dynasties before the invasions of the Persian, Greek, Roman and Arab foreigners. Second, whether their language, writing, vision of God and the universe, their concept of the divine kingship, ritual ceremonies and practices, administrative and architectural symbols, structures, and techno-complex, were quintessentially African and not, in any major particular, projected from those in Europe or Asia in that or any previous time. (105 illus.) |

|

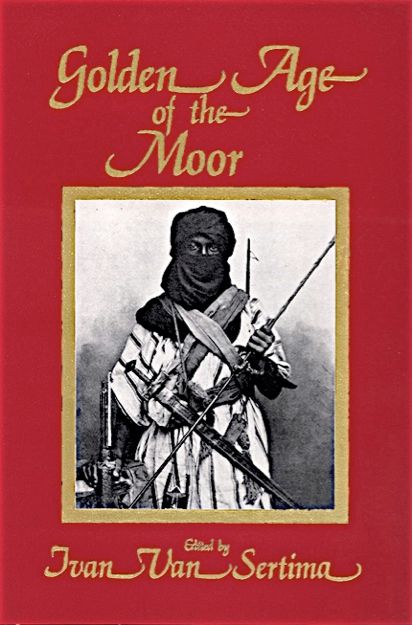

This work examines the debt owed by Europe to the Moors for the Renaissance and the significant role played by the African in the Muslim invasions of the Iberian peninsula. While it focuses mainly on Spain and Portugal, it also examines the races and roots of the original North African before the later ethnic mix of the blackamoors and tawny Moors in the medieval period. The study ranges from the Moor in the literature of Cervantes and Shakespeare to his profound influence upon Europe's university system and the diffusion via this system of the ancient and medieval sciences. The Moors are shown to affect not only European mathematics and map-making, agriculture and architecture, but their markets, their music, and their machines. The ethnicity of the Moor is re-examined, as is his unique contribution, both as creator and conduit, to the first seminal phase of the industrial revolution. (More than 100 illustrations) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

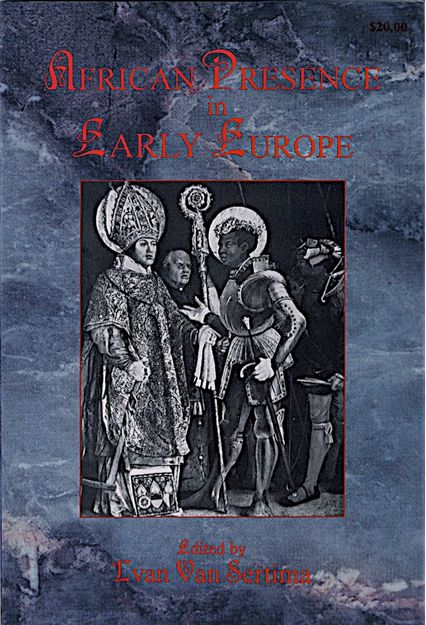

| This book places into perspective the role of the African in world civilization, in particular his little known contributions to the advancement of Europe. A major essay on the evolution of the Caucasoid discusses recent scientific discoveries of the African fatherhood of man and the shift towards albinism (dropping of pigmentation) by the Grimaldi African during an ice age (the Wurm Inderstadial) in Europe. The debt owed to African and Arab Moors for certain inventions usually credited to the Renaissance is discussed, as well as the much earlier Afro-Egyptian influence on Greek science and philosophy. The book is divided into six parts: The First Europeans; African Presence in the Ancient Mediterranean Isles and Mainland Greece; Africans in the European Religious Hierarchy (madonnas, saints and popes); African Presence in Western Europe; African Presence in Northern Europe; African Presence in Eastern Europe. (95 illus.) |

|

This book draws on the latest researches to show that Africa had an impressive scientific tradition in certain centers and historical periods. It highlights steel-smelting machines in Tanzania dating back 1,500 years ago, using semi-conductor technology and achieving temperatures 200 degrees higher than the best in Europe; an observatory in Kenya 300 B.C.; 13th century discoveries by West African astronomers of an invisible star, their accurate plotting of its orbit around its parent star as well as an orbit on its own axis, a fact unknown even to modern science; cultivation of crops and domestication of cattle 6,000-7,000 years before Asia or Europe; African first discoveries of tetracycline, vaccines, aspirin, as well as advances in operations like eye-cataract surgery and caesarean sections; African invention of half a dozen scripts before European colonization. The book also deals with African-American inventions, especially in the fields of telecommunication, space, and nuclear science. (96 illus.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This work is divided, with students and teachers in mind, into four sections. In the first section, two distinguished historians, Basil Davidson and Cheikh Anta Diop, present the evidence which establishes the African claim to a physical and cultural predominance in the classical Egyptian dynasties. The second section is a review of the major Black dynasties (Bruce Williams, Wayne Chandler, Runoko Rashidi, James Brunson, Legrand Clegg, Asa Hilliard, Phaon Goldman) and includes a working chronolgy of the dynasties. In the third section, Theophile Obenga initiates a rewriting of the beginnings of philosophy and Maulana Karenga provides a fresh study of the world's oldest treatises on social order. Charles Finch informs us of startling medical breakthroughs in his commentary on the Edwin Smith papyrus. The book closes with a bibliography of Black Women Scholars in Egyptology (Larry Obadele Williams), a guide to readings on Egypt for children (Beatrice Lumpkin) and a glossary of Egyptian terms (Rashidi and Blackburn.) (176 illus.) |

|

This volume, co-edited with guest editor, Runoko Rashidi, is divided into five sections. The first discusses the peopling of Asia from Africa and identifies African people with Asia's first hominid, as well as modern human populations. The second section deomonstrates the African elements underlying major early civilizations in Asia, an overview that includes India, Iraq and Iran, Phoenicia, Palestine, the Arabian peninsula, China, Japan and Cambodia. The third section discusses the African origin of the great religions of Asia—Judaism, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism. The fourth section focuses on the historical and anthropological relationship between African people and Asia's Indo-European, Mongoloid and Semitic populations. The final section deals with the African bondage in Asia and provides a fascinating glimpse of the Dalits, the Black Untouchables of India. Who are the Blacks of Asia? What have they done? What are they doing now? This volume seeks to answer these questions and to reunite a family too long separated. (More than 100 illustrations) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

35 years have passed since They Came Before Columbus was published. Dr. Van Sertima studiously avoided repeating his own work in this book. The Random House book is a work to be read by all. It is not only steeped in the history of an earlier time, and earlier Africa, and Earlier America, but an earlier style, charged withthe drama of ancient times, events and places, in spite of its groundwork in the facts of history. This book presents a number of facts that were not known over twenty years ago, but it is forged out of a burning desire to restate and update the case in the clearest possible manner. It is also forged and fueled out of an anger at the dishonesty of my critics and an overwhelming desire to set the record straight. These two books do not cancel out each other. It is as if they were written by brother-spirits, not by the same person.

As Dr. Van Sertima looked back at his earlier work, as if reading it for the first time, he looked over what he had already researched, and learned even more that established his work on an even firmer base. But these works, in no way, compete with each other, nor is Early America Revisited to be seen as a sequel to They Came Before Columbus. He was revisiting a house he never really left, a house of many floors, many rooms, some of which he had never lived in as fully during his first occupancy of the site.

Early America Revisited is a vigorous defense and ampification of Ivan Van Sertima's classic work, They Came Before Columbus. The book is a carefully balanced case for an African presence in America before Columbus' voyages, by Africans from the Mandingo empire of Mali, as well as for an Egypto-Nubian presence in both Central and South America before the Christian era. At the same time, the work is in no way a denial of the importance of the Columbus voyages for opening up the New World to Europe, and hence changing the economic and political map of the world for all time.

The critical cutting edge of the book is that there is an anthropological and ethnographic dimension to the precess of discovery; one in which black Africans of non-European origins played a central role. Van Sertima marshals the literary and pictorial evidence and shows its authenticity to be beyond question. The Pre-Columbian period is not just a mater of dating, but of discovery. The impact of these early discoveries are of far more than historical interest. They serve as a basis to examine anew the study of culture contacts between civilzations. And in so doing, offer a serious base to a multifaceted re-examination of earlier hypotheses of influences in both directions.

Van Sertima makes it plain that Early America Revisited is more than a stack of evidence about the physical presence of Africans in pre-Columbian America. It is the study of how two peoples and cultures can lead to cross fertilization. But it also indicates that the borrowing of artifacts and ideas does not constitute a claim that the outsider is superior to the native, or that indigenous cultures are insignificant. He does contend that such relationships can be unpleasant as well as pleasant, conflictual as well as consensual. But, whatever the character of the interaction, its very existence merits awareness.

This is a book likely to engender further disputes and disagreements. But there is no question that it will enrich the study of a wide range of subjects, from archaeology to anthropology, and result in profound changes in the reordering of historical priorities and pedagogy. It should be of wide interest to social scientists, historians, and all those for whom the question of race and culture is a central facet of their own work and lives. |

|

|

Text

Text

|

Shopping Basket

Note: All prices in US Dollars

|